|

Trích từ trang web: |

|

Joseph Freinademetz SVD Pioneer of the Divine Word Missionaries in China |

|

“The only language Joseph Freinademetz

Joseph Freinademetz – |

|

Joseph Freinademetz – A Saint?

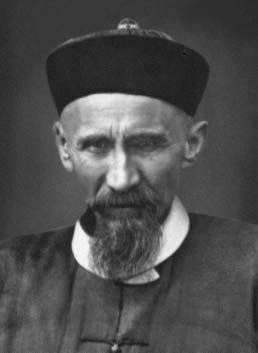

Saint Joseph Freinademetz was not an obvious leader. He did not found a religious order and he never became a bishop; he was almost always in second place. He did not write a significant theological treatise, nor did he develop any new mission methods; he did not die a martyr but, like many others in China, fell victim to a typhus epidemic. Why would the Church canonize such a man? When he died, one Chinese man said, “It is as if I had lost father and mother!” He had come to love the people, ‘his’ Chinese people - love them so much that for their sake he never wanted to return to his own country. He wanted to be buried among them and even to be counted among them in heaven. Joseph Freinademetz is a ‘saint of charity’, as the Church puts it. “When we speak of self-realization, the Christian must think of realizing Christ,” said Pope John Paul II. The Church calls the saints “friends of God.” According to a Latin proverb: “To want the same thing and to reject the same thing, that is friendship.” Joseph Freinademetz lived that kind of friendship. He wanted what Christ wanted, and he rejected whatever he could not square with God’s will. At the beginning of his ministry in South Shandong he wrote, “I am alone in the midst of a completely pagan people. Deo gratias. But what will I do here, what can I build? Dear God, you build, otherwise I will build in vain; you do battle, you stand watch, otherwise I watch in vain! May the harvest indeed be great, but … God wills it! So set to work!”

“I do not regard being a missionary

Joseph Freinademetz SVD—Missionary from Steyl

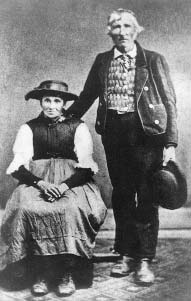

Arnold Janssen, with several companions, founded the first Catholic mission house for Germanspeaking regions in the Dutch village of Steyl in the fall of 1875. The humble beginnings bordered on real poverty. However, its farsighted and attractive press apostolate soon made the Mission Institute of Steyl well known. The European “mission fervor” of the times rapidly transformed Janssen’s modest initiative into a significant missionary order: the Divine Word Missionaries. News of the young Mission House in Steyl reached the distant mountain valleys of South Tyrol and struck a chord in the heart of the young curate, Joseph Freinademetz. His wish to become a missionary had already formed during his seminary days and he lost no time in acting. In January 1878 he saw the article about the Steyl Mission House in the Brixen diocesan bulletin. At the end of August he moved to Steyl, and in March 1879 he traveled with John B. Anzer to China. Freinademetz and Anzer were the first two missionaries to go out from Steyl. Joseph Freinademetz became a missionary not in Steyl, but rather in China – and the process was very personal and at times painful. At the end of that process he no longer regarded the people of China as objects whom he was sent to baptize, but people with and among whom he wanted to live God’s love, making that love tangible. That is the enduring legacy of his life – for the missionaries of Steyl and for the entire Church. Son of the Mountains EARLY YEARS Joseph Freinademetz was born on April 15, 1852, high up in the Dolomites of South Tyrol, in the tiny hamlet of Oies that belongs to Abtei, Badia. Abtei is the main town of the upper Gader Valley. Today Alta Badia, as it is known, attracts crowds of tourists and skiers. In Freinademetz’ day it was an almost inaccessible, narrow mountain valley where people barely scraped out a living. The people of the Gader Valley and neighboring valleys belong to a small minority group, the Ladins, who still today speak a Romance language of their own. When Joseph Freinademetz was born, the Dolomite valleys belonged to the canton of Tyrol that had been part of Austria since the 14th century. In 1919, after World War I, the southern part of Tyrol, including the Gader Valley, was given to Italy by the vanquishing powers. The Freinademetz family had a small farm. Joseph was the fourth child; nine others, four of whom died soon after birth, came after him. Oies lies at an altitude of 1500 meters where not much grows, apart from grass. Half a dozen cows, a few pigs, some sheep and a horse were the economic mainstay of the Freinademetz household. Daily life was deeply rooted in Catholic tradition. The day commenced with the ‘Angelus’ and closed with the family rosary before the house altar. From spring to fall, Joseph’s father, Giovanmattia, made a weekly pilgrimage up to the ancient chapel of the Holy Cross, 2000 meters above sea level. Every day he took the children to Mass in the parish church of St. Leonard’s, twenty minutes from Oies. |

|

After four years of elementary school in St. Leonhard’s, little Üjöp, as Joseph was called in his Ladin mother tongue, was sent to school in the bishop’s city, Brixen, on the advice of the parish priest. It was an 11-hour walk for there were hardly any roads in the Gader Valley in those days. In Brixen only German was spoken and Joseph’s knowledge of it was scanty. Today, alongside Ladin, people in the Gader Valley mainly speak Italian. After two years at a German elementary school in Brixen, he was able to transfer to the high school. Although not otherwise an academic high-flyer, Joseph Freinademetz showed an excellent talent for languages.

PATH TO THE PRIESTHOOD

In 1872 Joseph entered the major seminary. Prince Bishop Vinzenz Gasser of the Brixen diocese had played a significant part in the First Vatican Council. The small, bishop’s city was also pervaded by a surprising missionary spirit; it was open to the world. At high school and in the seminary, Joseph Freinademetz had teachers who cultivated lively contacts with missionaries. The idea of becoming a missionary one day doubtless germinated there. In 1875 he was ordained. A year later he completed his studies and was appointed curate to St. Martin’s in his home area, the Gader Valley, where his main task was teaching. Meanwhile the idea of a missionary vocation took firm root.

VIA STEYL TO CHINA |

|

Tyrolean View of World and Church

Then Joseph Freinademetz went to Steyl, it was the first time he had traveled beyond his native mountain valleys; he was 26 years old. His life, habits, world view and idea of the Church had been formed by the small, intensely Catholic world in which he grew up. Church moral teaching determined both private and public life, the course of theyear was defined by the liturgical calendar. Its fidelity to the Church had earned Tyrol its reputation as a ‘holy land.’ In 1837, Protestants were still being driven from their homes in Tyrol because of their beliefs. Prince Bishop Vinzenz Gasser of Brixen fought with all his might against the religious freedom the Viennese government had managed to assert, offering his resignation to Pope Pius IX because two Protestant parishes were established in his diocese in 1876. The parishioners of St. Martin’s greeted their curate with “Praised be Jesus Christ,” and the children kissed his hand. A dominant theme in his often rather long sermons was ‘sin and hell,’ as was customary at the time. That was the ‘thoroughly Catholic’ world in which Joseph Freinademetz was at home. |

|

When the son of the mountains of Tyrol landed in Hong Kong in April 1879, it was with the intention from then on “to convert the poor pagans and root out idolatry and unbelief.” In a sermon at St. Martin’s he had declaired, “When I think of those unfortunate lands and peoples where the darkest night of paganism reigns, where the true religion is unknown, of those people who are also our brothers and sisters, my heart beats passionately, and tears well up in my eyes.” In his farewell sermon he said, “I know the surpassing misery of our brothers across the oceans who, with tears in their eyes, stretch out their hands toward us, imploring help.” “Outer Transformation”

From the narrow vales of Tyrol to cosmopolitan Hong Kong things were bound to go awry. About 1000 of the 140,000 Chinese inhabitants of Hong Kong were Catholic. Of the approximately 10,000 strong, mixed foreign community: English, Portuguese, Americans, French, Germans, Spanish, Filipinos, Indians and Persians; very few could be bothered with the Church. Then there was the tiny, dirty fishing village of Saikung where he had to learn the language and where he was stricken with malaria and digestive disorders. All in all, it was no place to gather storms of enthusiasm.

LONELY AND DISAPPOINTED

Externally, Joseph became Chinese. His name became ‘Fu Jo-shei Shenfu’, simplified to ‘Fu Shenfu’ – Lucky Priest. His reddish blond hair was shorn except for a crop at the back to which a black pigtail was fastened. The black cassock from Europe gave way to a blue Chinese robe. Cloth shoes replaced the leather ones, but his view of things remained European, Tyrolean. The mission church was rather shabby. He described the pagoda at the foot of the hill as magnificent, and he watched enviously as people went in and out. All he had was an old Chinese man who was trying to teach him the language. |

|

Since Fr. Piazzoli, the Italian missionary in Saikung, took advantage of his presence to visit the outstations, he was on his own for weeks at a time. It was a depressing situation. Six months later when they exchanged roles and he was the one to sail from island to island, trek from village to village, visit the few, scattered Christians and try to arouse the interest of others for his faith, he was mainly unsuccessful. People came to see an exotic European, not to listen to his message. And worst of all they shouted, “Foreign devil!” after him. He had renounced family, friends, home, everything to free the Chinese from the clutches of the devil – and now they were calling him ‘devil’! It jarred on his ears and cut him to the quick. For his part, he began to see the devil at work everywhere. For him temples were houses of the devil; the religious festivals were festivals of the devil; the devil was venerated with firecrackers and canons; sacrifices were offered to the devil. Summing it all up he wrote, “China is well and truly the kingdom of the devil. You can hardly go ten steps without coming up against all kinds of hellish images and every manner of devilry!” His personal disillusionment gave rise to wholesale judgment abounding in prejudice: “The Chinese character has little that appeals to us Europeans… The Creator did not endow the Chinese with the same qualities as the Europeans. … The Chinese are incapable of higher motives.” |

|

Without being aware of it, he felt betrayed by the illusions he was clinging to. This the young missionary felt most bitterly. He wrote about himself: “He comes from Europe aflame with zeal; he hopes that at nightfall his arms will drop limp and tired at his sides after long hours of preaching and baptizing; that every year a few more pagodas will crumble in ruins before his eyes, thus making room for so many more houses of God” – and instead …? Joseph Freinademetz was a man of his times and his country. There was no room in his view for other religions. To be a missionary meant to win souls for the Catholic faith. That did not succeed to the extent he wanted, so he was disappointed and frustrated.

“Inner Transformation”

Personal disappointments, difficulties of physical adjustment and the frustrating lack of success forced Freinademetz to face the basic existential questions and reflect on his vocation. The thoughts he expressed could not have come to him overnight. He must have spent much time brooding, meditating and praying before he wrote the lines he entitled The Missionary’s Joys: “If ever there was a great work on earth, great because of its sublime goal, admirable because of the quantity and quality of its means and successes, it is the religion of the Crucified and the apostolate inseparably connected with it… In this light everything takes on a new, quite unique hue; what is small and unimportant becomes singularly attractive, what is bitter gains a peculiar sweetness. The quiet solitude and general loneliness speak to the heart of the missionary in a unique manner, and since the more we are alone, the closer God is to us, the missionary does not know whether in such a situation he should cry because of inner hurt or shout for great joy, and so he does both.” Not words of mature old age; Freinademetz was 28 years old and full of energy and plans when he wrote these almost mystical lines at the end of his two years in Hong Kong. He himself described those two years as his “mission novitiate,” two decisive years during which he found the spiritual ground and foundation on which he could build his life in China. Chinese clothing did not turn Joseph Freinademetz into a new man. He recognized that and realized what had to be done: “The main work still remains: transformation of the inner person: to study the Chinese way of thought, Chinese customs and usages, Chinese character and disposition. All that cannot be achieved in a day, not even in one year, and also not without some painful surgery.” |

|

With those words, he had formulated his life plan without actually realizing it. He began to free himself from his narrow thinking and became a graced missionary. He was eminently well equipped to build up the first mission of the Divine Word Missionaries in South Shandong. Joseph Freinademetz left Hong Kong in 1881. The Chinese language of Shandong is different from that spoken in the former British Crown Colony, so after new language studies, he arrived in Puoli in March 1882, in what was to become the main station of the new mission. South Shandong was not just his field of work, it became his home.

Itinerant Missionary

Freinademetz worked in South Shandong as he had in Saikung. In a vast region that had scarcely been visited by a European, he walked from village to village, for weeks, sometimes months, at a time accompanied by a faithful, half blind Chinese companion. He did this once during the first two years, then after four years; but later he was almost constantly traveling in whatever capacity, whether as a simple missionary, Pro-vicar, mission administrator or provincial and visitator. He walked, rode a donkey or horse, or traveled in a sedan chair or a one-wheeled cart pushed by a wagoner. He got to know the region like few others, and not only the region, but above all the people. From then on he began to do what as a young man in Hong Kong he had seen to be the main thing; Fu Shenfu studied “the Chinese, their way of thought, their customs and usages, their character and disposition.” He did not study merely out of curiosity or for objective purposes, he was not just collecting knowledge of customs and habits on his endless wanderings and travels. Rather it led to what he had already regarded as necessary while he was in Hong Kong, namely to the ‘transformation of the inner person.’ The more he got to know the Chinese and their language and culture, the more he came to esteem them, and the more reverently he spoke of them. It even came to the point where he could not stand it if anyone spoke derogatively of ‘the Chinese.’ His attitude was not without criticism, it contradicted the secular, and partially also the ecclesial, spirit of the times. |

|

1897 “with an iron fist.”

|

|

German Governor von Truppel |

|

The Spirit of the Times

By the second half of the nineteenth century European colonialism was at its height – and the ancient Chinese Empire had sunk to the lowest point in its history. England, France, Russia and also Japan forced the weak and crumbling Kingdom to accept unfair trade treaties. The fledgling German Empire sought desperately for an opportunity to follow suit. The murder of two German missionaries, confreres of Joseph Freinademetz, in South Shandong in unclear circumstances, gave Kaiser Wilhelm II just the excuse he was looking for. Protection of German missionaries in South Shandong served as the pretext for the occupation of a region that had long been in German sights and was selected out of economic interest, namely Kiaochow Bay with the harbor city of Tsingtao. The German Kaiser sent his soldiers on their way with the order to “storm in with an iron fist” if the Chinese did not submit. |

|

The occupying forces used their military superiority to exploit China. The Chinese people were humiliated, and local officials whipped up hatred toward all foreigners. The missionaries were identified with intruders who wanted to destroy Chinese culture and tradition and the Confucian power structures. To be truthful, not all the missionaries were blameless when it came to racist tendencies and some manifested a European arrogance towards the Chinese. |

|

“… for your Chinese …”

In August 15, 1886, Freinademetz took final vows. With its first General Chapter, the community in Steyl had become the ‘Society of the Divine Word’ that very year. Joseph was 34 years old and had been in China for seven years, four of them in South Shandong. “Thus I vow to you, holy Triune God…” are the words of the vow formula. For Freinademetz, however, the vows were not only his interior, unconditional, total commitment to the Creator. Through them he bound his life inseparably to the people of China. He not only offered his strength, his energy and his life for them – “pray, work, suffer…” – he also bound his life after death, his hope of eternal happiness, to them. That is, he could not even imagine life in heaven without the Chinese. He confided to his diary: “With this, brother Joseph, the die is cast: pray, work, suffer, endure. Your whole life for your beloved Chinese, then when you come to the evening of your life and lie on your deathbed, you can sleep surrounded by your dear Chinese. Adieu! Farewell forever dear homeland beyond the sea!”

BECOMING A CHINESE TO THE CHINESE

Joseph had come to love the people, his ‘dear Chinese’. When he was preparing for vows he had written home: “I assure you honestly and sincerely that I love China and the Chinese… Now that I have less difficulty with the language and know the people and their way of life better, China has become not only my homeland but also the battlefield on which I will one day fall…” Although the ‘battlefield’ comparison sounds strange to us nowadays, we can understand his meaning, namely that he was not committing himself to an idea, and not just for the Kingdom of God in general, but for these specific people with whom he dealt day in, day out, for those whom he loved; not in some kind of supernatural sense but for themselves. He wrote to his sister: “I want to live and die with the Chinese.” Not everyone appreciated his attitude. To some, his affection for the Chinese people and everything Chinese appeared exaggerated. But his first biographer, Henninghaus, who later became bishop and who had worked with him for many years, stressed time and again that Freinademetz was by no means blind to the faults and weaknesses of the Chinese people. Henninghaus compared his affection with the love that Paul proclaimed in his letter to the Corinthians: “Love is always ready to make allowances, to trust, to hope and to endure whatever comes.” His love had to ‘endure’ not a little. Freinademetz himself complained more than once that he was constantly being cheated and deceived: “How often have the Chinese got the better of me!” Fr. Heinrich Erlemann, who at times was very critical of Fr. Freinademetz, wrote after his death: “I would dare to say that no missionary in our mission experienced such cruel ingratitude from the Chinese at times than the greatest friend of the Chinese, namely Fr. Freinademetz.” For Fr. Erlemann it was incomprehensible that Fr. Freinademetz still kept his affection for them. A Tyrolean countryman of Fr. Freinademetz, the Franciscan Fr. Zeno Koeltner, considered such a view of the Chinese simply incompatible with his mandate: “How can the man hear confessions when he regards these people as such saints!” Fr. Erlemann even thought he could distinguish a specific point in time for his confrere’s special affection: “In the years 1886 to 1890 he declared the Chinese to be perfectly holy, with the distinction that they were not baptized and did not believe in God.”

AFFECTION

It was precisely during those four years that the inveterate missionary was especially close to the Chinese. He was again traveling, trekking from village to village. Usually he had to stay in one or the other shabby inn or primitive farm hut. There were so few Christians and catechists that Freinademetz moved mainly among people who were directly inimical to him. He heard himself mocked for his ‘long nose’ and he heard his religion ridiculed. It was just at this time, according to Fr. Erlemann that he was so uncritical with regard to the Chinese. That view smacks more of personal fault-finding than unbiased observation! Such situations, the unvarying daily round and close contact cannot be romantically glossed over, nor overcome by pious fiction. Fu Shenfu’s affection and love for the Chinese must have been genuine and deep.

“True virtue is made possible |

|

A Tender Heart

Even if he demanded so much of himself, shirked no effort, led an ascetic life, and limited and sacrificed his personal needs, Freinademetz had anything but a tough nature. On the contrary, he was a sensitive, sometimes oversensitive and an emotional man who could shed tears. The farewell from home and parents, for instance, was extremely difficult. When the “dear school children” at St. Martin’s cried at his words of farewell, “it pierced my heart,” he wrote, and he continued, “I would rather not describe the farewell scene in my parents’ house…” Before taking vows, he had directed the mission in South Shandong as administrator in Anzer’s absence and had taken care of the Christians in Puoli and the surrounding area. He had become attached to them, it was difficult to say goodbye: “This time my eyes did not succeed in staying dry; euntes ibant et flebant – they went out weeping!” The good Christians of Puoli “had begun to grow too close to my heart….” |

|

Candidly he admitted how letters from home touched him: “It is not homesickness…, but a strange feeling that causes my tears to flow.” When the German Empire occupied Tsingtao and he was again administrator in the absence of the bishop, Joseph celebrated High Mass for the soldiers and was so overcome by the “expression and precision” with which the military band played their “pious songs” that “our eyes almost filled with tears.” When they sang Te Deum at the end of Mass, his self-control collapsed completely; one saw how “tears rolled down the pale, lined cheeks.” His letters are full of lively descriptions and examples that clearly show the very human manner in which he sympathized with the fate of his Chinese people. Yet his gentle nature by no means prevented him from remaining firm at decisive moments and expressing his opinion. Fr. Erlemann admitted, “I had quite a few conflicts with him, but if the matter did not agree with his view, there was no way out, no matter how good your intention might be.” |

|

When he had to write visitation reports, clarify difficult situations, describe the character of individual missionaries and decide who was suitable for which task or office, his judgments were anything but a favorable gloss. They were undeniably objective and sober. “The little that we do

Scrupulous?

Even those who viewed him critically admitted that Fr. Freinademetz made radical demands on himself, especially in his consistent living out of apostolic poverty and obedience. To live with him at close quarters was not everyone’s choice, to be sure. Fr. Anton Volpert described it from the viewpoint of experience: “It was a great good fortune for me to have the saintly Pro-vicar as superior and teacher. But it was also a misfortune. Confucius already pointed out that it is more difficult to get on with the perfect than with the less perfect. I was still too imperfect and he required too much of me.” In the young religious Congregation he had a good reputation. When new missionaries arrived they were curious at first about this ‘godly’ man. European visitors, travelers and diplomats were just as impressed by his personality as the soldiers and officers of the German occupying forces. People admired him and wondered at his radical manner of thinking and living. He was convincing even for those who did not share his faith and his views. But how did he see himself? When there was talk of calling him back to Europe for a senior position, he described himself in a manner that is almost a confession. He saw himself obliged to “open his innermost heart so that Father Rector [A. Janssen] will know what a miserable subject you are dealing with.” After the request not to regard his open confession as false humility, he allowed a look into his most intimate self, wrote that in his thoughts he had problems with sexuality, and then described his character: “I am terribly vain and conceited; I am moody and dejected when things don’t go according to my will; on the other hand, unrestrained and unpleasantly ironical when things are going well. I quickly become unwilling and impatient and sometimes even put the catechumens off through my example. In no way do I have control over myself and I often give in to the lure of passions.” Did he really see himself that way? Not one of his confreres saw him in anything like that light. That he was humble in the truest sense of the word was confirmed by all. It is possible to detect a tendency towards scrupulosity in some of his descriptions, a tendency that found expression during his final days when he made his confession several times, even though bedridden and physically weakened. He was not the only one who was convinced that God had to be given a detailed account of every single matter; it was in line with the contemporary spirituality when he said: “If the account doesn’t square, it will have to be paid in purgatory, usque ad ultimum quadrantem, right down to the last penny.” That may also have been the reason why he feared death. But when he came to that point, he passed peacefully. “When one has fulfilled one’s duty and done all that was possible, God will surely be merciful … How great to be a Catholic. How peacefully one can die.” His last words show his absolute and unconditional trust in the power of the sacraments. He was just as convinced of the effectiveness of a priestly blessing and holy water to which he ascribed an almost magical power: “I could tell you many things about this young mission, e.g. about the wonderful effect of holy water that has already healed the sick here and immediately driven out devils from those possessed.” He had written that for publication in Steyl and it is significant that it was not printed literally. For his personal attitude it is also significant that he wrote in that connection: “I do not find it remarkable that the evil spirits flee; Christ gave his Church power over them. But that the poor pagans see these signs and cannot understand them, that grieves me!” – Joseph Freinademetz was a missionary through and through, he was concerned for the people, for ‘his’ Chinese!

Did he want to be a Martyr? |

|

The Christian missionaries were a real thorn in the side of the local Chinese authorities, who hindered the mission wherever they could. They skillfully manipulated the general xenophobia and stirred up the masses against the foreigners time and again. Fr. Freinademetz experienced that several times. In May 1889 he was severely maltreated and left half dead. On November 1, 1897 two young missionaries, Richard Henle and Franz Nies, were stabbed to death. The Steyl mission mourned its first martyrs. With the Bishop out of the country, Fr. Freinademetz, mission superior, stood before the coffins deeply shaken. In 1900 the political situation in China became critical when the Boxer uprising broke out. The missionaries were ordered to retire to the safer coastal areas. During these critical months, Freinademetz, who as Pro-vicar was responsible for the entire mission while the bishop was away, was concerned for his people – and he wanted to remain there himself, to take care of the orphans and the Christians who had fled to the main mission station of Puoli. His confreres protested. His response was, “But why should I not sacrifice myself? I am half dead already and will soon die anyway. My life is of no importance anymore, whereas you can still do a great deal for God.” It was true, physically he was not in good condition; years of austerity were making themselves felt as Joseph approached fifty years of age. His kidneys were causing trouble, he had a chronic throat ailment and had been coughing up blood for quite some time. The doctors diagnosed TB and said he would not live much longer. That was his condition when the order to evacuate came. His health had even worsened dramatically in the previous few days. At first, he let his confreres persuade him to go with them, but he turned back after 20 km. He could not be at peace. This time the confreres let him go. They were sure they would not see him again.

NOT WORTHY OF MARTYRDOM?

When things calmed down, he reported to Steyl that he had prepared the Christians in Puoli for a “bloody death” and for “honorable and graced martyrdom.” “The good Lord saw how much they prayed and wept; those who did not experience it themselves cannot imagine the feelings.” To an old school friend he wrote: “How many tears and how much blood have flowed in our unhappy China. I myself, whom you thought dead long ago, am still alive, although for months I hung between life and death. Humanly speaking, there could hardly be a thought of escape and even my confreres reckoned me among the damnati ad mortem … All that has passed and I am still alive because I was not worthy of martyrdom. How many bishops, missionaries and Christians have earned a martyr’s crown and I was cast into the junk room as a ‘useless object’!” What he wrote there sounds honest, the more so because he changed the subject with an anecdote: “How am I? Well, thank God; I have also put an end to spitting blood. A confrere wrote to me from Tsingtao that I really ought to stop coughing up blood because when the Tataohui came to slaughter me and only water flowed out instead of blood, it could cause great difficulties at the beatification process (!!!)” – He wrote the three exclamation marks himself. |

|

Forever in Second Place

As long as Bishop Anzer was alive, Freinademetz always took second place, with brief exceptions when he had to substitute for the Bishop. That was the case when Anzer was out of the country. Up till the bishop’s death Freinademetz was in charge of the mission for about five years. In addition there was the period when the See was vacant and another two years when the new bishop was out of the country. Was Freinademetz born to be in second place? When the two first missionaries departed from Steyl, it was clear that Anzer would be the superior. When the Franciscans handed the South Shandong mission over to the Steyl missionaries, Anzer was appointed Pro-vicar by the competent bishop, admittedly after some skirmishing. Bavarian born John Baptist Anzer was a rather impetuous character; it was not in his nature to tread quietly. When the borders of the new mission territory had to be delineated, he became embroiled in a conflict with the Apostolic Administrator. |

|

The latter then wished to appoint Freinademetz as Pro-vicar, i.e. as his representative. It was obvious that before long South Shandong would become an apostolic vicariate in its own right and the pro-vicar would become Vicar Apostolic, i.e. bishop. Freinademetz was alarmed and begged the Bishop, literally on his knees, to appoint Anzer. Was that only an act of humility?

Augustin Henninghaus, his collaborator of many years and first biographer, confirmed that the South Tyrolean missionary had an “open, clear and sober judgment,” “good common sense,” a “natural ability to evaluate a situation and a sober, objective grasp of things.” These natural abilities helped him to judge himself well. He would not have been the right man to build up the mission in South Shandong as superior. Arnold Janssen, the founder in Steyl, also saw it that way: “Freinademetz is genuinely pious and has an amiable disposition, he is zealous and not wanting in prudence, but he is less qualified than Anzer to be superior.” Freinademetz was a pastoral man, his strengths lay in interpersonal relations, while Anzer loved the limelight and was “firmer, more enterprising and stronger” (Arnold Janssen). Janssen advised Anzer to include the Tyrolean “in especially delicate negotiations,” counsel that Anzer often followed.

“Let us see life for what it really is:

It is part of the tragedy of these two pioneers of the mission in South Shandong that they did not get on well together and grew continually further apart. Their characters were too different. Added to that, over the years Anzer developed a problem with alcohol, became estranged from his fellow-missionaries, and made arbitrary decisions at short notice. It went so far that Freinademetz was urged by his confreres to request the removal of the bishop. Dramatic scenes took place between them. Anzer accused him of being soft and of plotting intrigues against him. The reproach hit Freinademetz hard but he did not retreat. Death [in November 1903] finally saved the bishop from demotion. The ‘natural’ successor would have been Joseph Freinademetz, at least, that is how the Society’s founder, Janssen, and the majority of the missionaries saw it. Did he see it that way himself? He knew he was a candidate for the post, but we can believe him when he says he did not want to be bishop; his commonsense was still functioning. His words on the subject to an acquaintance were quite drastic: “You think I would become a bishop; you are barking up the wrong tree. A miter doesn’t fit a blockhead and no one would place one there. Added to that, alongside many peccata personalia I also have the peccatum originale that is not washed out by any waters of baptism.” The peccatum originale, ‘original sin,’ was his Austrian nationality. The German government had made it clear to the Vatican that they wanted a German national as bishop, and they specifically rejected Freinademetz. He was outraged, certainly not because he wanted to be a bishop, but because nationality ought not to be deciding factor for the Church! The Imperial German government doubtless had other reasons: Freinademetz had repeatedly complained about the way the colonial authorities lived and the manner in which they treated the Chinese people. On top of that, as Henninghaus reported, the missionary from South Tyrol had declared to no less a personage than Prince Henry of Prussia, the Kaiser’s brother, that the occupation of Tsingtao “was not in accordance with the principles of justice.” Obviously his affection for the Chinese caused him to dispense with diplomatic niceties. |

|

Provincial

In summer 1900, when the Boxer uprising had been put down and the missionaries had returned to their stations, Arnold Janssen appointed Joseph Freinademetz as provincial, i.e. the superior of the missionaries who were members of the SVD Society. Until then Bishop Anzer had combined the office with that of his episcopate. Anzer took the new appointment as a personal affront and at first refused all cooperation. Freinademetz remained in office until his death and he took his responsibilities very seriously. He regularly visited his confreres, kept up a brisk correspondence with the Society’s leadership in Steyl, and constructed a central house in Taikia on a large piece of land. From Steyl he had gained the agreement that the members of the Society of the Divine Word were to spend at least one month each year in the central house. He couched the explanation to his confreres in terms that sound rather flowery to modern ears: “Since as the representative of our most Reverend Fr. Superior General it is my duty to take the bull by the horns, as it were, and as St. Paul says in his first letter to the Corinthians (14:8): ‘Si incertam vocem det tuba, quis parabit se ad bellum?’ ‘If the bugle gives an indistinct sound, who will get ready for battle?’ I will outline briefly and concisely the primary reason why we come here and the finis primarius, what our stay in Taikia is meant to be for us. What is that reason? ‘Ut renovetur uterque noster homo!’ Spiritual and physical recreation and refreshment so that with renewed strength we may strive for the unum necessarium. Therefore it should first of all be as comfortable as possible here and secondly, as useful as possible.” He had been in China long enough and knew his confreres too well not to realize the necessity of improved interpersonal relations, spiritual refreshment and theological updating. As provincial he made use of the opportunity offered by those four weeks for an in-depth, confidential talk with each one. He conscientiously sent an annual report to the general administration. Whereas in 1901 negative observations took up a great deal of space, his view became far more positive in subsequent years. Significant criteria for his judgment of his confreres were the manner in which they dealt with the local population and how they kept their vow of poverty. He rigorously forbade his confreres to buy expensive ‘European things’ without his specific permission. He was happy that fewer and fewer of them were wearing “rich silk Chinese clothes.” He expressly pointed out that “the principle of authority has been thrown deeply into confusion.” The reason was obvious. In Steyl, too, they were well aware that it was a consequence of Bishop Anzer’s unpredictable administration. “MOTHER” OF THE PROVINCE

Provincial Freinademetz gave his confreres the feeling that the religious congregation they belonged to was concerned for their welfare in every way. And the majority of his men were grateful to him. In his concern for the spiritual well-being of his confreres he kept both feet on the ground; that can be seen from the list of topics for his talks. They dealt with an explanation of the Society’s rule about clear accounting and thrift, registration of land property, supervision of building activities – as far as possible adjusted to the Chinese style – and even a tree-planting program for barren hillsides. Caring for his confreres gave him new zest as well; his health greatly improved. In 1902, at the age of fifty, he became more and more the calm center of the South Shandong mission, finally becoming the ‘Mother of the Province’. The appointment of Augustin Henninghaus as the new bishop in 1904 initiated an exceptionally fruitful collaboration between bishop and provincial. The final four years of the missionary from South Tyrol were probably the most peaceful and also most enjoyable of his life.

|

|

Versatile – By Necessity

Freinademetz had many talents but he was not a genius. If we go through the data of his life and the list of his various ministries, however, bearing in mind that he was far too conscientious to do things by halves or rely on improvisation, it is apparent that he was enormously industrious. His tenacity and his ability to manage with relatively little sleep were a distinct advantage. The needs of the moment, i.e. mainly the lack of personnel, to say nothing of trained personnel, and not least his unquestioning obedience to John Baptist Anzer, often obliged him to undertake activities and occupy himself with topics that he would certainly not have chosen. Personally he liked most to be with the catechumens and neo-Christians; with them he positively bloomed. He was heart and soul a pastoral minister. Yet he hardly once had the chance to remain in one place or one area longer than two years at a time. Time and again the bishop sent him on visitations that required detailed written reports. If there was a new area where the Church was to take root, the bishop found no one better to send than him. For a time he directed the catechists’ courses, and for one year the major seminary, as well. The first diocesan synod had to be prepared and suitable topics worked out. Following that, the provincial chapter was convened and he once again had to take care of the written work. The orientation of new missionaries fell to him as did the preparation of young missionaries for their final vows. He frequently gave retreats. In between all that he still found time to publish a Chinese catechism and to work out rules for catechists. Then there were the countless letters to family, friends and benefactors at home, as well as the brisk correspondence with the general administration in Steyl. Due to his good knowledge of Chinese, the bishop frequently asked him to take care of the correspondence with local officials. He had to invest an enormous amount of time in negotiations with Chinese authorities. There were also obligatory visits to Chinese and German officials and diplomats which required the observation of strict rules of etiquette. For one such as he, who felt more at home in a farmer’s shack than in a salon, that must have been a special burden.

“Let us remain unafraid in all dangers,

There were great distances to cover with each move, either on horseback or by primitive means of travel. South Shandong was a vast region, the Yellow River often a formidable barrier. There were journeys of up to eighty hours – and Freinademetz had severe health problems at times. It is striking that there is little indication that he felt overburdened or that he did not have enough time for anyone; quite the contrary, all who met him were impressed by his friendliness and the way he devoted all his attention to the one he was talking to. The first Chinese cardinal, Thomas Tien, experienced it himself: “He was always there for others and then he was totally there just for them, completely selfless and forgetful of himself.” How did he manage all that?

AT THE SERVICE OF HIS CALLING

Joseph Freinademetz’ spirituality was down to earth and integrated. He could incorporate tasks that did not much appeal to him into his spiritual vision and he placed every facet of his life at the service of his vocation. That became evident, for instance, when he explained to his confreres the purpose of the one-month sojourn to the new central house in Taikia: “Our life is too short, our time too precious to lose even a tiny second of it! This month, too, belongs to God, and God will place each of its 720 hours, each of its 43,200 minutes, each of its 2,595,000 seconds on the scale of his justice, and demand an accounting from us.” With this admonition to make careful use of time he was by no means referring only to mental or spiritual work: “Nevertheless a really thorough-going rest and recuperation is part of our stay in Taikia. Body and soul are two diametrically opposed things, like fire and water. Still, the one is dependent on the other. When the body no longer cooperates, the soul also ceases to function, its activities die down as when a fire lacks fuel or the electricity for a machine is shut off.” He was never at a loss for analogies.

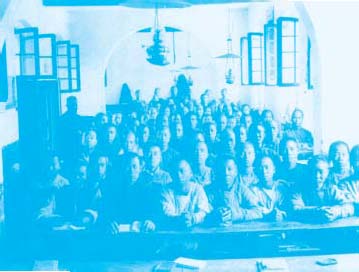

Among the Catechists and Local Clergy

Freinademetz thought a great deal of the catechists. They were the backbone of the mission, as both he and Anzer had learned in Hong Kong: “These catechists get on much more easily than we do. They are Chinese, whereas we are called ‘European devils’.” In South Shandong they had a kind of double role at one and the same time: if people from a locality expressed interest in the Christian religion, a catechist was first dispatched there to clarify matters and only after that did a missionary go to visit. It could also be the other way round; a foreign priest aroused curiosity and then the catechist remained in the locality to continue the work. The majority of small communities in the villages were headed by a catechist.

THE MISSION OF THE LAITY

Freinademetz regarded the catechists as more than just helpers of the missionaries. To him they were genuine apostles, and as community leaders they shared in the pastoral mandate. In 1893/94, as director of the catechists’ training courses, he compiled a rule specifically for them (in Chinese and Latin). There he wrote first of their vocation: “Remember this! God chose you especially from among so many!” He regarded the necessary commission by the bishop as a sign of unity and at the same time a mandate to share in the Church’s pastoral and teaching ministry: “When you now go out to proclaim the faith, are you not in truth apostles of Christ? When the people are going astray like sheep without a shepherd, you are to help and pasture them.” When we reflect that the majority of the catechists had only been baptized for a few years, we can gauge the measure of trust placed in them. All the greater, of course, was Fr. Freinademetz’ disappointment when catechists neglected their duties or gave up their faith.

He viewed their task within a broader context: “After the time of the great emperors and the great wise men, the old virtues are beginning to disappear in China. Serious-minded persons are looking out for people who, like the apostles of Jesus, preach and show the right path. You, dear Catechists, with your proclamation are the fulfillment of the hopes of many.” His efforts with regard to their training corresponded to the great significance he attributed to them. In reference to the time when he was director of the catechists’ training course he wrote: “I can say that during the past fifteen years in China I have never been so overloaded with work.” As Administrator after the death of Bishop Anzer, he insisted that the catechists come together for several weeks each year for further training and ‘spiritual exercises.’ Joseph Freinademetz was especially close to an elderly catechist named Wang Shuo-sin who had been a Taoist monk. For many years Wang was his secretary and personal adviser. He was particularly indispensable during negotiations with authorities because he was extremely well versed in oral and written communication with officials. |

|

The missionary from South Tyrol had a similar trusting relationship with the local priests. In his preparatory paper for the diocesan synod, he requested equal status for them: “Chinese priests are not second-class priests. For them as for the European priests there is but one order of precedence – the length of service in the mission. All Church offices and dignities must be open to the Chinese priests in the same way as they are to the European priests without any discrimination.” In 1902 he asked the superior general to admit the Chinese priest Hsia to the Society “and to altogether open the door for Chinese aspirants.” Arnold Janssen still hesitated. Church leadership hesitated even longer: It was decades before Rome appointed the first Chinese bishops. Only in 1946, was Thomas Tien SVD, who as a seminarian had known Freinademetz, elevated by Pius XII to cardinal, the first non-white cardinal.

“Prayer is our strength, our sword,

Man of Prayer

Freinademetz was what one would call a ‘great man of prayer,’ and a ‘spiritual’ person. In his preparatory work for the first diocesan synod of South Shandong, his fundamental attitude became clear in the synod paper on “The Clergy.” “Do you imagine you can become holy without meditation, something no saint was able to do? Meditation is a waste of time? The very opposite is true. Without meditation life is lost. Furthermore, set aside one day a month for prayer and meditation. Such days are among life’s most beautiful and enriching. On such days the Holy Spirit has promised to speak to our hearts.” Just to see him at prayer was edifying for many: “Mostly he knelt in the sanctuary of the church; and for us it was an extraordinary experience to see him at prayer. The image of that kneeling priest is indelibly impressed in my memory. You got the impression that nothing could disturb him. He was a great man of prayer. His piety was open and aroused fervor” (Cardinal Tien). Henninghaus states straight out that “Prayer” was his “life element and life’s joy,” it was the “source from which he lived.” Even when he had to work until late at night, he still took time for prayer and spiritual reading. In summer, Freinademetz often began his working day at 3 a.m., with prayer and meditation. He preferred to pray the breviary kneeling, mainly very erect without any support. He may often have recalled his childhood when the whole family knelt every day on the hard boards of the living room, praying the rosary before the house altar. |

|

He celebrated holy Mass “in a dignified and devout manner, without haste but without irritating slowness” (Henninghaus). The man from Tyrol obviously did not wish to be importunate in these things either. The official name of the Steyl missionaries, ‘Society of the Divine Word’, fitted as if tailored made for him: “Daily spiritual reading. Do not let even a single day pass without meditating on sacred scripture which has been called the Priest’s Book. Woe to you if the well-springs of devotion in you run dry!” he exhorted in one of the synod papers. He himself knew the Bible inside out. He frequently quoted scripture, mostly in Latin, and above all he was always able to find suitable comparisons for current situations; i.e. he had truly internalized the Bible. It was not a dead letter for him, not ‘dry,’ but full of life, a well from which he knew how to draw water. With the same intensity he challenged his confreres to continue to update themselves: “Cultivate serious study! Sacred scripture says, ‘Because you have despised wisdom, I will despise you’.” That, too, is an example of the way in which he could quote the Bible. |

|

Cross and Suffering in the Life of Joseph Freinademetz

The Cross and Christ’s sufferings were images that accompanied Joseph Freinademetz from his earliest years. His home area is at the foot of the ‘Kreuzkofel’ (Cross Summit). Directly below the steep mountain walls, Stations of the Cross, that are still in use today, lead from all directions to the ancient sanctuary of Holy Cross. His cousin Maria Algrang could remember how the student and young priest “very often” made the pilgrimage there. The miraculous image venerated at the sanctuary, a wood carving of Christ carrying the cross, is still carried up in a solemn procession after the snow thaws and brought down again to the parish church of Abtei in October. To the catechists whom he had to instruct in 1893/94, Freinademetz said, “There is one path all have to take if they wish to become saints. I mean meditation on the bitter suffering of our Lord Jesus.” Once he began to interiorly work through his disappointments and failures no longer ascribing them in frustration to the character of the Chinese, he spoke of the Cross: “The entire Passion repeats itself in the life and history of the Church… The Church has to traverse a week of the Passion here, sweat blood in the Garden of Olives, die on the Cross, she has constantly to struggle and fight, to work and suffer, to endure and to bleed. Bloody and bloodless martyrdom is her constant characteristic.” That also applied to Joseph himself. He saw personal setbacks and humiliation, disappointments over catechumens again defecting from the faith, etc., as well as persecution, as his share in the way of the cross. Not everyone could understand this. In his obituary for Fr. Freinademetz, Fr. Erlemann wrote: “He did indeed work and suffer very much and earn a rich crown of merit … I cannot conceal the fact that many of his sufferings had their roots in his natural disposition. Another man would not have brought such suffering on himself.” Erlemann’s explanation for that statement was the fact that Freinademetz was so often deceived by the Chinese but had learned nothing from it – in Erlemann’s view – because he fell into the same trap time and again. Perhaps Fr. Freinademetz’ serenity, patience and empathy, which grew greater year by year, had their roots in his knowledge that his life was tied to his Lord’s way of the cross. On the other hand he was greatly loved by the Christians: “The Christians love their missionaries as much as in Europe and even more. For that, one happily bears a few crosses.” His heaviest cross, however, must have been the recognition that the majority of the Chinese people, ‘his’ Chinese, would not come to faith in the cross of Christ and thus, as the theology of his time taught, they could not find salvation. Was that perhaps the reason why he was prepared to accept martyrdom, to sacrifice his life for their salvation? He would have been capable of that, for some of the most frequently repeated words of Joseph Freinademetz are: “I would like to be Chinese in heaven!” That probably means: In heaven he would like to have as many Chinese around him as possible!

Oies – a popular place of pilgrimage today |

|

JOSEPH FREINADEMETZ COMES HOME

“As a tree needs the earth to give it life and nourishment,” said Joseph Freinademetz, “the soul needs prayer.” He will be happy to see that over the past 50 years his birthplace has become increasingly a place of prayer, meditation and quiet recollection, as well as a place of pilgrimage. Each year thousands flock there. Well beyond the frontiers of Tyrol, Joseph Freinademetz has become a trusted intercessor in many situations of need. A small community of Divine Word Missionaries lives in the house in Oies; they are there for the pilgrims, to provide the possibility of recollection and encounter with Saint Joseph Freinademetz. In 1995 a church was constructed to take large groups of pilgrims. In this way, Joseph Freinademetz, the missionary who became a sign of God’s goodness in China, has come back to the world of his beloved Tyrolean mountain home. |

|

PIONEER OF THE DIVINE WORD MISSIONARIES IN CHINA |

|

J.F. |

Significant Dates |

|

April 4, 1852 |

Joseph Freinademetz born in Oies, Abtei, South Tyrol |

|

1858-1862 |

Ladin primary school in Abtei |

|

1862-1876 |

German primary school, high school and Philosophy/Theology in Brixen |

|

July 25, 1875 |

Priestly ordination |

|

1876-1878 |

Curate at St. Martin’s in the Gader Valley |

|

1878-79 |

Steyl |

|

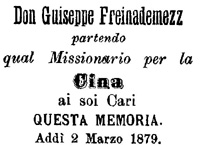

March 2, 1879 |

Mission-departure celebration, farewell to his home country |

|

1879-1881 |

Saikung, Hong Kong |

|

1882 |

Arrival in Puoli, South Shandong |

|

1882-1884 |

Itinerant missionary |

|

1884-1886 |

Mission administrator |

|

August 15, 1886 |

Final vows |

|

1886-1890 |

Itinerant missionary |

|

1890-1891 |

Mission administrator |

|

1892 |

Coordinator of the Diocesan Synod; visitation tour |

|

1893-1894 |

Director of catechist courses |

|

1895-1897 |

Director of the major seminary |

|

1897-1898 |

Mission administrator |

|

Nov. 1, 1897 |

Murder of Fathers Nies and Henle |

|

Nov. 14, 1897 |

Occupation of Kiaochow Bay by German troops |

|

1898 |

New mission stations in the east of South Shandong |

|

1899-1900 |

Mission administrator (1900 Boxer Uprising) |

|

1900 |

Appointment as Provincial |

|

1903-1904 |

Mission administrator |

|

1904-1907 |

Working with Bishop Henninghaus; Provincial center established in Taikia |

|

1907-1908 |

Mission administrator |

|

Jan. 1, 1908 |

Death of Joseph Freinademetz in Taikia, South Shandong |

|

Oct. 19, 1975 |

Beatification of J. Freinademetz and A. Janssen by Paul VI |

|

Oct. 5, 2003 |

Canonization of J. Freinademetz and A. Janssen by John Paul II |

|

1852

|

|

|

|

|

Oies (group of houses, center) and the villages of St. Leonhard, Pedraces and Stern in the valley, below the towering, almost 3000m high Holy Cross Peak |

|

|

|

|

1875

|

|

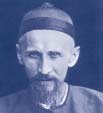

The newly ordained Joseph Freinademetz. |

|

|

1879 the son of Tyrol’s

|

|

|

|

|

“Fu Shenfu” – Lucky Priest. |

|

|

1890 |

|

Joseph Freinademetz to one of his brothers. |

|

|

1900 the political situation in China became critical, |

|

1901 the missionaries of the |

|

1902 central house in Taikia. A place of encounter, rest and renewal. |

|

|

Title page of |

|

1898 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

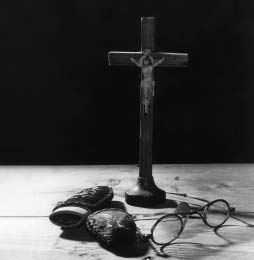

The cross of Christ, the Eucharist and contemplation of God’s Word |

|

|

|